Someone once told me that being Native is not easy. I did not understand why until I researched my own family history and discovered what happened to my Dakota and Nakota ancestors. Women were forced to abandon traditional ways of life, assimilating into the white man’s world. Generations later, I am a result of that assimilation, a descendant with centuries of ancestral trauma running through her veins. Indigenous women bear the brunt of settler colonialism. Too often, they are dismissed and forgotten by society. This erasure must stop. They can teach us the true history of the land we reside on if we choose to listen. Their stories will encourage more women to speak about injustices in their communities. The women photographed have taught me about preserving traditions, protecting land and water, caring for community, coming to terms with my own colonial trauma, and celebrating my Native heritage.

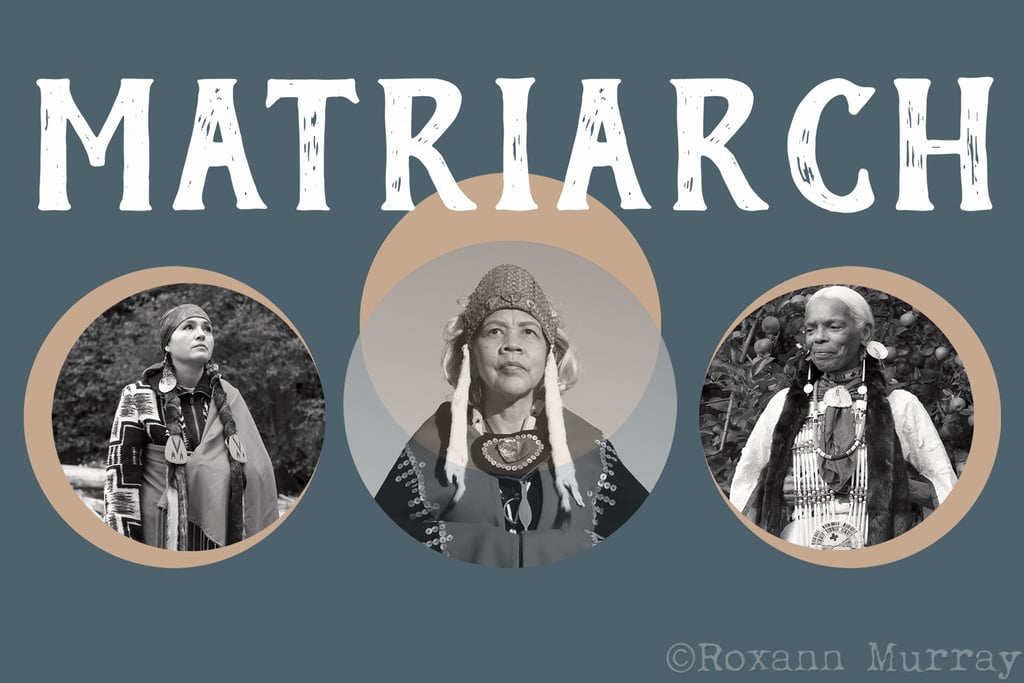

Portraits of Indigenous Women Fighting for Our Collective Future

Mariana Harvey

Yakama

As a young adult, Mariana became involved with harvesting traditional foods and bringing those foods back to the Native community. Learning plant medicine and her Native language became priorities. She looks to the land and water as the holders of knowledge and abundance when times are difficult. Mariana sees Indigenous women as natural organizers. We are the core of our families. We are the caretakers of not just our families, but also of the Earth.

Nancy Shippentower

Puyallup, Tulalip

Nancy grew up playing with her siblings and cousins along the Nisqually riverbank. During the Fishing Wars in the 1960s, and Nancy’s family was at the epicenter of it. Her father was jailed for catching fish to feed his family. Her mother was jailed for defying state game wardens. Nancy’s teachers harassed her because they were sports fishermen. She learned how to be a leader from her parents. They taught her to speak up for what is right and be independent.

Sweetwater Nannauck

Tlingit, Tsimshian, Haida

Sweetwater grew up in Alaska, and was raised by her Tlingit grandparents. She ate traditional foods and lived off the land and water. Her grandfather taught her to always be proud of where she comes from. Sweetwater has dedicated her life to protecting the land, water, and Native communities. She encourages the next generation to stay close to the Elders. Sweetwater hopes her life has exceeded the prayers her grandmother said for her.

Paige Pettibon

Bitterroot Salish

Paige’s grandmother created a sense of place, home, and belonging. She now honors these themes in her art. Paige witnessed addiction and the tragedies that come with it in her family; this encouraged her to break cycles of trauma. Paige stresses the importance of true community and sisterhood when at times there is only a façade of togetherness. She focuses on being mindful with the connections she makes.

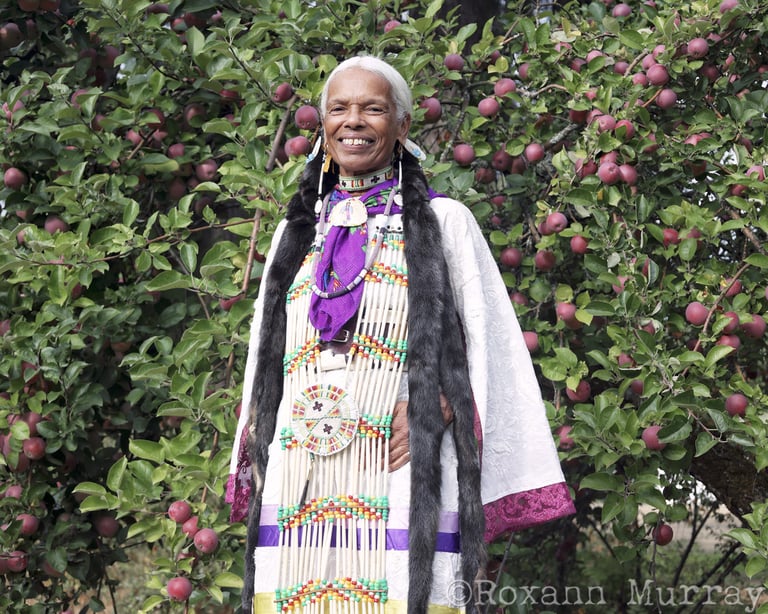

Carolyn Christmas

Mi’kmaq

As a multiracial child in Nova Scotia, Carolyn always had questions about her identity. Even though Carolyn’s mother hid their cultural identity, Carolyn still grew up eating traditional foods and heard her mother occasionally speak her Native language. She once asked her mother, “What are we?” because she felt her family did not fit in. Her mother’s response was “We are human”. Carolyn stresses that it is important to know where you come from and to love who you are.

Elizabeth Satiacum

Quileute

As a young child, Elizabeth became a ward of the state during the 1960’s Scoop Era. This caused a disconnection between her and her family. She experienced the same traumas that children in boarding schools experienced, but on a one-to-one scale in the foster system. None of this dimmed her sense of humor and she never gave up hope. She encourages young people to learn their traditions and speak up against injustices.

Lisa Fruichantie

Seminole

Growing up in Alaska, Lisa learned at a young age that we must never take nature for granted. She lived off the land and sea with her family. Everything changed once Exxon Valdez’s oil spill; the ecosystem was destroyed and her community could no longer support itself. This pivotal moment in Lisa’s childhood opened her eyes to the importance of protecting the environment, including the communities that rely on it for subsistence.

Janene Hampton

Syilx, Okanagan

Janene did not have the benefit of growing up in a traditional way; her grandmother was disenfranchised after marrying a settler. It wasn’t until the movement at Standing Rock when Janene went back to her roots. She stayed for six months until the military destroyed the camp. When she came home, she wanted to learn how to live off the land and be more connected to nature. She now spends much of her time with family on her ancestral homeland of Penticton, BC.